LOG STRUCTURES OF THE EARLY SETTLERS

Homestead consisted of half a lot, a 75 acre land parcel, marked by surveyed lines cut through the bush and identified by axe blazed trees. At each corner, where property lines intercepted, was a rough axe hewn square post, with concession and lot numbers carved into it.

Homestead consisted of half a lot, a 75 acre land parcel, marked by surveyed lines cut through the bush and identified by axe blazed trees. At each corner, where property lines intercepted, was a rough axe hewn square post, with concession and lot numbers carved into it.

After a homestead had been chosen and claimed, a building site would be selected – preferably an area of higher ground, with tall white spruce, poplar and birch stands. The popular dense black spruce stands identified the low land, the ground being too wet with too much moss and black muck to build on. Considerations also had to be made regarding access to future main roads, neighbours and other community functions. Minimum government specifications and standards were quite simple – the structure be no smaller than 16 ft. x 20 ft., and that latrine and other out buildings sheltering animals be a minimum of 75 ft. from the source of drinking water.

The site of the initial structure would be laid out and staked, usually parallel to surveyor lines or future roads. Brush, moss, roots and some topsoil were removed. Usually some subsoil was mounded and leveled under the first set of base logs. Concrete or other masonry materials were not available. The substructure was placed directly on the bare ground, with bark often still remaining on the logs. (Buildings constructed in later years would have a substructure of peeled logs, treated with creosote).

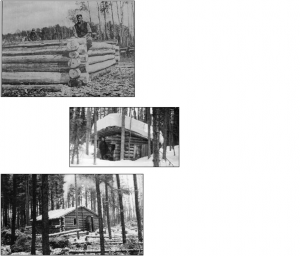

Since the principal building materials were logs, the source was not a problem, trees were plentiful and selection was good. The thickness was generally from 8 inches at the butt to 5 inches or so, at the crown and typical of a 24 foot log. As each log was placed, it would be notched at each corner of the structure, to receive the next set of logs. The notches were open to the top (a practice that our people were to change in later years, as they learned the proper way to build log structures from the Finlanders – the notches then were to be open to the bottom). Gable ends too, usually were vertical logs, held together with 8 inch spikes. To tie the gable structures together, special selected stems would be placed for purloins and ridge, to which thinner poles were attached corduroy style. (Later as it became available rough sawn lumber was used for this purpose). Tar paper over thinly spread sphagnum moss on this crude roof deck was meant to keep it all dry, however I remember the many tin cans, carefully placed in the attic and emptying them after every time it rained.

After the walls had been erected, door and window openings were cut into them. Doors were made of stockade poles or lumber with ‘Z’ braces on them. Dad had attached a thick curved stick on the outside, at the bottom. His arms loaded when be carried in firewood, he would hook his foot into it, to open the door. The windows often had no sash. The glass pane was simplyputtied against a rough lumber frame. If any windows did open, it was essential that they also had mosquito screens.

Some of the early settlement houses had corduroy pole floors and stockade partition walls in them. Of course lumber was used if it was available, accessible and affordable. In later years, inside log walls got covered with rough sawn boards and papered with untreated construction paper. Some people even used printed wallpaper and painted the lumber floors. The houses were heated with wood burning stoves. Elmira combination cooking and heating stoves were popular. Wood was fed in through heavy lids in the flat cast iron top, or on other models through a side door. At the bottom of the burner was the grate, and below that a damper, in a cast iron door that opened to remove the ashes. The oven was to one side of the fire chamber. Some deluxe models had a small hot water tank, or also a built in warmer oven over top of the unit. Since wood was plentiful, houses were easy to heat, providing the wood was dry. In the winter the outside walls were banked with snow, sometimes as high as hallway to the roof eaves. Our houses were cozy and warm. Airtight houses however, would cause heavy floral frosting on single pane windows during cold winter weather.

Another heating device was the ‘Quebec Heater’, a high risk stove because of its thin gage metal construction. Stoves constructed from oil barrels were also used in some buildings. The log church building in which we worshiped on Sundays had one. Henry Lepp, tells the story of how he would go early Sunday morning to light the fire in the church stove. Then, when he had a roaring flame in it, making the stove vibrate and jump, the pipes turning red from the extreme heat, he would damper it down. Then he would take off his parka and wildly flail it in a circular motion, in an attempt to distribute the heat. However when the people came, they would still find it cold to sit on the wooden benches. They would keep their coats on and crowd around the stove. It would never fail that some one would get too close to the hot stove, trying to warm up their cold behind, suddenly causing the stench of singeing fabric and smoke rising from the back of his coat. Adding to the embarrassment, the poor soul would then get a proper slapping from others, mattress, covered with sheets, sewn together from empty 100 lb. flour sacks. Duck feathers and down made warm blankets and cozy pillows. Other log structures were the barns and perhaps some outhouses. No homes had indoor plumbing. Schools, churches and other public buildings were log structures as well. As a boy, I remember lying in my bed, listening to the constant crunching sound of the wood beetles under the dried bark of the spruce logs beside my bed. I would pick some bark off, exposing the channels filled with wood dust. The creatures I saw, doing the fancy woodwork, actually were not beetles but grubs, using their whole bodies as they rhythmically gyrated and bored their way into the wood. Although these early settler log structures offered shelter, warmth and a crude, simple comfort, the construction practices and the manner in which they were built, limited them to a temporary time span. Adding the ever-present risk of fire, the habitable time of twenty years may well have been the exception, rather than the norm.

MILE ONE-O-THREE

Lyrics by Dennis Wiens

The train dropped off its load No matter how much strength

On mile one-o-three A faith in God had shown

The people stood no house no home With meagre yields the spuds don’t grow

A homestead made of trees On muskeg soil and stone

“I’ll guarantee a place to live So when the trees were gone

Don’t stop and be perplexed No axe in future plans

I’ ll take a place under this pine The people left their empty homes

And you can take the next.” For further fruitful lands….

God’s nature was a sight The train no longer stops

A glory to behold On mile one-o-three

With sun and snow aurora high The people left no house no home

The hearts were made of gold Now nature’s running free

The pioneers they hoped Foundations made on other lands

A community of one They gather in the summer sun

Then others came and lent a hand The memories shared, the memories fade

And boundaries were undone Still praising God the one.

CHORUS:

They made a home

The trees were felled

A life was made with praises raised

In God their faith was held

They made a home

The work days long

A life was made the living hard

In God their faith was strong

THE LITTLE LOG CHURCH

The little log church at Mile hundred and three

On Sunday morning, is where we would be

To worship and pray and sing with joy

A long time ago, when I was a boy

The kind folks of Reesor would share and love

The blessings of God, that came from above

In summer we’d walk, in winter we’d ski

But every Sunday in church we would be

The building was plain it had no steeple

The little log church of the Reesor people

However there was no place we’d rather

On Sunday morning worship together